History and Philosophy

Introduction

A quick glance at some of the important milestones in the Award’s past helps to understand how the existing Award structure and requirements have evolved. What underpins the Award, or its philosophy and ethos, is also a helpful basis to appreciate why the Award plays such a significant role in many people’s lives. Finally, this chapter will look briefly at the Award’s constitution, highlighting the key elements which guide the delivery of the Award.

History

The original idea came from the same man who thought up Outward Bound and Atlantic (now United World) Colleges and Round Square. Kurt Hahn had been a Rhodes Scholar and Private Secretary to the last Imperial German Chancellor before becoming a schoolmaster. He founded a boarding school at Salem in Germany and then, having fled Germany in the early 1930s, founded a school named Gordonstoun in Scotland.

It was at Gordonstoun that The Duke of Edinburgh completed the Moray Badge, a direct precursor of the Award and something that Hahn felt could be used in many more places than just his school. However, the Second World War prevented further development and it wasn’t until the early 1950s that Hahn made approaches to The Duke of Edinburgh to establish a national badge scheme based on the old Moray Badge idea.By 1954, The Duke of Edinburgh agreed that, if Hahn could get a representative committee together to give their approval to the general idea, he would be prepared to take the position of Chair. The Duke was also joined by Sir John (later Lord) Hunt, the leader of the first expedition to conquer Mount Everest. A first draft of the idea appeared in 1955 which was sent to voluntary youth and other relevant organisations. These discussions resulted in a scheme being launched, initially in an experimental form for three years.

The original aim was to motivate boys aged between 15 and 18 to become involved in a balanced programme of voluntary selfdevelopment activities to take them through the potentially difficult period between adolescence and adulthood.

Within the first year of its establishment, the lower age limit was reduced to 14, where it has stayed ever since. A girl's scheme was launched in 1958, and the two separate schemes were amalgamated in 1969. In 1957 the upper age limit was increased to 19, increased again in 1965 to 20, increased to 21 in 1969, and finally increased to 24 in 1980.

Since 1956, the Award has developed and grown and now reaches young people in over 140 countries and territories under a number of different titles, for example The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award in the UK, The President's Award in Kenya, and The National Youth Achievement Award in Singapore. More specific national titles are also used, for example Prémio Infante D. Henrique in Portugal and Avartti in Finland. Full details of the Award’s presence in any particular country can be found online at www.intaward.org.

In May 1988, The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award International Association was formally constituted to act as a means for discussion and communication between members, and to uphold the principles and standards of the Award. In 2012, the full name of the organisation was changed to The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Foundation.

Today the basic principles of the Award have endured, but the activities and delivery continue to evolve and adapt to suit the changing demands of today’s world and the varying needs of young people.

The Award is now recognised as the world’s leading achievement award for young people and is used by organisations working with young people around the world. It is therefore important that the Award remains relevant to young people and their communities and that it empowers them to be able to tackle the challenges they face, and have a positive impact both on themselves and their communities.

Philosophy

The Award is about individual challenge. As every individual is different, so too are the challenges that young people undertake to achieve their Award. With guidance from their Award Leader, Assessor or other Award volunteers, each young person should be encouraged to examine themselves, their interests, abilities, and ambitions, then set themselves challenges in the four different sections of the Award. These challenges should require persistence and determination to overcome.

Along the way participants may feel daunted or want to give up, but at the end will have the satisfaction of knowing they overcame the challenges and succeeded, learning about themselves, their hidden depths of character and developing as human beings in the process.

It is important that these challenges are at the right level for the individual participant – too easy and there will be no sense of real achievement, too difficult and the young person may give up in despair.

Young people do not need to excel to achieve an Award, they simply need to set personally challenging goals for improvement and then strive to reach those goals. A demonstration of commitment will help a young person get out of the Award what they put in: essentially, there are no short cuts to a real sense of achievement.

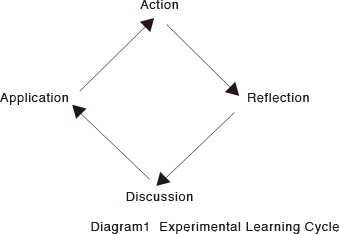

Finally, to help young people overcome their fears and challenges, the Award provides them with opportunities to learn from experience. Kurt Hahn, among others, helped to develop the philosophy of ‘experiential learning’, a process of making meaning from direct experience.

The aim of education is to impel people into value forming experiences... to ensure the survival of these qualities: an enterprising curiosity, an undefeatable spirit, tenacity in pursuit... and above all, compassion... It is culpable neglect not to impel young people into experiences.

Kurt Hahn